Random comments about culture and life from Joseph Bosco, formerly Hong Kong/now St Louis-based anthropologist.

Monday, October 30, 2017

Arbitrage or scam?

NPR's Planet Money recently replayed and updated a 2014 show called "Free Money" about two guys in Utah who buy used textbooks online at the end of semesters, when students are selling their books and prices are low, and then re-sell them at the start of the semester when prices are high. From a certain point of view, they are providing a service: they help make the market in textbooks work by buying and selling them. They also take a risk, because they store them for months and the books may not have a market the next semester (if, for example, a new edition or a better textbook comes out). But some people do not like what they do; one woman saw it as just jacking up the prices on her daughter's textbooks. The Utah guys are doing classic arbitrage, the taking of advantage in price differences between two markets, and it has always been controversial. If after a hurricane, I drive to the stricken area with a truck full of electric generators and sell them for five times what I paid for them, some will say that I'm offering a service (after all, without me, the generators are not available at all, and in any case, no one is forcing the buyers to buy from me) and others will say I'm profiteering and behaving immorally by taking advantage of other people's distress. Both arguments have validity and it is sometimes difficult to balance the two ideals of a free market and our sense of a "fair price".

The two friends selling books are able to make money and run their business because they post their books on Amazon.com, which creates a marketplace; without Amazon, it would be much more difficult to find these two guys who are selling a fairly small number of books. Theirs is not a big business. They are not like Abe.com, or my favorite, BetterWorldBooks.com (which is run as a social enterprise, meaning they do not try to maximize their profits; it also happens to be run by a graduate of my alma mater, and near my home town in Indiana). These bookstores, as far as I can see, do not raise their prices at the start of the semester, but run a store with stable prices. They do not do arbitrage; they are the market.

Last week, I ordered two air mattresses on Amazon, because we will be having a lot of guests over Christmas. They arrived over the weekend, but I was shocked to find that they arrived in a Walmart.com box. I was sure I had not bought them from Walmart. I remembered that I had to search long and hard to find what I wanted, and that I had bought them not from Amazon directly but from a different Amazon-affiliated vendor, "Posh Products USA" (Amazon page here). So why did the mattresses come from Walmart? At first I was confused.

The answer was in the bottom of the box, on the receipt, which had several surprises. First, it showed that my mattresses had been ordered by "Monica McCoy" to be shipped to me. I have never heard of or met Monica McCoy. Second, Monica only paid $7.97 each for the mattresses, and the total order came to $21.93 for two mattresses including shipping and handling. I paid $17.03 for each mattress, for a total of $34.06 (I'm not sure why I was not charged sales tax on that). So Monica made $12.13 in arbitrage profits, and she never touched my mattresses. She simply took my money, and turned around and ordered the mattresses from Walmart.com for me.

This seems very odd; it is odd that such a gap (i.e. arbitrage opportunity) even exists in this age of digital data. And I can't help but feel a bit cheated: why did Amazon not give me a lower price? The two men in the NPR story actually bought the books, stored them, and shipped them themselves. But Monica is just trolling for buyers. In fact, she may not have placed the order for the mattresses at all; if she's clever, her computer is set up to automatically place the order on Walmart when a sucker like me places an order with Monica. Well, now I know: before shopping at Amazon, I need to do comparison price shopping at Walmart and Target and other stores.

The Amazon page for Posh Products USA (which is a ridiculous name that should have given me pause!) shows that Monica sells a wide variety of products--obviously whatever she can identify an arbitrage opportunity in. There is a leaf blower, candy, a shaver, cat food, and on and on, 2168 products in all. Here is a "business" that may make money but is hardly providing any social value (it is helping people discover cheaper items, but charging more for them than someone else does, who is also able to ship it to you!)

I can't help but feel a bit taken advantage of, because Monica's only service was listing the mattress on Amazon.com. I suppose she researched this, and I should be thankful that she is sharing the savings with me. But it seems to me that the fact that the product never passed through her hands is what makes this arbitrage a bit more distasteful than most.

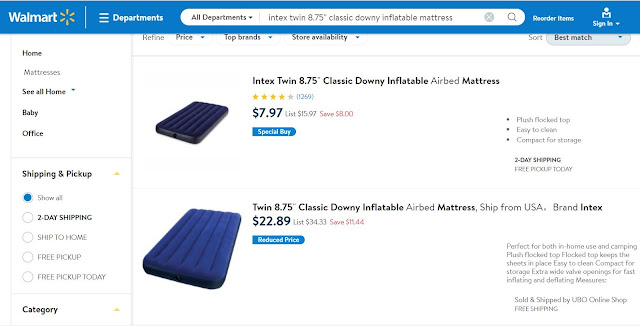

One additional curious aspect of this story is that on the Walmart website, there are two prices for the same mattress that I bought. One is the $7.97 price, and the other is $22.89. The first is a "Special buy" and the second is "Reduced Price" (providing more evidence that marketing terms are meaningless). The list prices of the two mattresses are very different, too, but the mattresses are the same (they look like they are different colors in the online photo, but the $7.97 mattresses I received are the blue color like the $22.89 mattress, so I'm sure they are the same). So we can see how Monica set her price; it is half-way between her price of $7.97 and the "full" price of $22.89.

I'm just glad I did not go on to the Walmart.com site and buy them at the higher price.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

Post a Comment