I also remember that the whole class read a book about a boy that hunted bears. I remember that some classmates liked the book so much that they read it multiple times (reading a book multiple times is something I’ve never been tempted to do; there are so many new books to read!). Though I remember being really taken by the book, and remember that the stories were based on life in Indiana back in the frontier days when there were wild bears running about, I did not remember the title or author, or the plot. A decade or so ago I asked my old 4th grade friend if he remembered the book and knew the title, but he did not remember it.

|

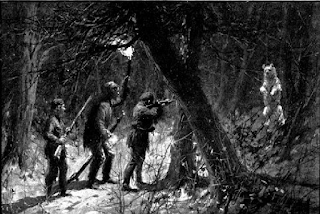

| Balser & Tom shot wolves and caught cubs |

|

| Balser shooting a bear |

|

| Liney saves Balser |

And there is a love interest; the neighbors (who live several miles away) have a daughter, Liney Fox, and she and Balser both like each other. Balser saves her from being kidnapped by an Indian, and in a later chapter, she saves his life by putting a flaming torch in the face of a bear that was mauling Balser. Early in the story, Balser is given a gun as a gift by a stranger he helps, and he goes out hunting with it. He hunts to kill scary bears, and to provide food and pelts for the family. His hunting is described as “sport and recreation,” and like the trips to gather nuts in the fall sound like a lot of fun. These are the kind of adventures American boys grow up dreaming about—at least in mid-20th century Indiana.

Reading the book as an adult (I don’t think this counts as re-reading the book, like some of my classmates did in 4th grade!), I notice that while the tales of hunting bears are fun and dramatic, they are totally unrealistic. Even in the 1820s, I doubt parents would allow their 14 year old son to organize a hunting party with a friend (the friend only armed with a hatchet) to kill a large bear that is so large, fierce and frightening that some people claim it is demonic. In addition, Balser is mauled by bears twice, and bitten on his foot one more time, and yet only suffers 2 broken ribs and wounds that heal in a couple of weeks. Frankly, I’m skeptical. But it makes for some good stories.

Another aspect of the book that I notice is the aspect of the supernatural. The “one-eared bear” (AKA “demon bear”) appears suddenly, as though he sprang from the earth, and similarly, disappears suddenly, so Balsar and his dogs do not see where it went. This “magic” is not explained in the book, but the bear is later spotted again, and dispatched, ending speculation among most residents that it was a demon. In another case, a “fire bear” glows like fire in the night. The chapter ends:Many of the Blue River people did not believe that the Fire Bear derived its fiery appearance from supernatural causes. They suggested that the bear probably had made its bed of decayed wood containing foxfire, and that its fur was covered with phosphorous which glowed like the light of the firefly after night.

|

| The firebear |

The book also begins a story that involves an explosion with

a note, like an epigraph, that states:

Note: The author, fearing that the account of fire springing from the earth, given in the following story, may be considered by the reader too improbably for any book but one of Arabian fables, wishes to say that the fire and the explosion occurred in the place and manner described.

At the end of the chapter, the author explains that this explosion was

caused by a “pocket” of natural gas that was ignited by a torch. Thus, the

author is hinting at the supernatural, but insisting that in the end there are

natural explanations for all these unusual phenomena, even though, as in the

case of the one-eared bear, he may not always know how to explain them.

The fire bear, the author tells us, was blamed “by many persons, especially of the ignorant class,” for fires that broke out in haystacks and barns. Balser dismissed such ideas and believed Indians started the fires, but “seeing is believing,” so was convinced it was a “fire bear” once he saw it. The author later tells readers that the bear glowed because it had laid in some phosphorescent bacteria, so was not "on fire" at all.

|

| Tom shoots the firebear |

The charm worked at least one spell. It made the boy braver and gave him self-confidence.

This is a common argument in research on magic: that it serves primarily (and perhaps only) to give confidence in the person using the spell or amulet. In the book, the author describes the beliefs, creates tension and lets the reader wonder, but in the end shows that natural explanations are best.

One cannot help but wonder whether stories we read in our youth influence and shape us. In this case, I’m amused to see a children’s book from 1901 that reflects my current “academic” views on the supernatural. The fact that my views match this author’s also suggests that my views are not new at all, but over a century old, and merely reflect Western modernism.